Thoughts before bed with Criminal Law finals in 29 hours

Motive for this piece

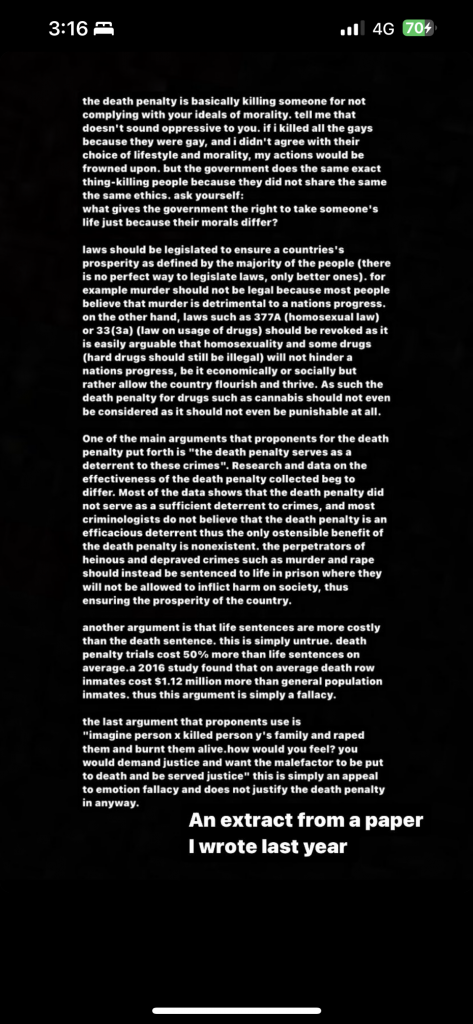

I’ve increasingly frequently been seeing protests against Singapore’s death penalty on social media platforms, whether it be on TikTok or Instagram (the two I use most often). Most recently, I saw this story:

…the author of which I leave unidentified. Rest assured, story poster, none of this is personal – I mean you nothing but the respect afforded to every human being.

I believe this perceived sudden uptick of outrage/condemnation of the death penalty on social media can partly be explained by the spike in executions in 2022 as compared to previous years. In 2022, 11 individuals were killed, compared to an annual average of 0.67 taken over the three years preceding (2020-2022).1

The current position/situation

Capital punishment, as of the rules being currently in force, is applicable to thirty-three crimes2.

Cases that pop up in the news and on social media usually relate to either drug [trafficking] offenses or murder, so this is what I will focus on most.

Understanding when courts give capital punishment

Before I jump into any arguments for/against the death penalty in general, it’s important to have a rudimentary understanding of when courts even give capital punishment in the first place. I’ve seen some arguments premised on flat-out incorrect facts, even if made with the best intentions.

Murder

Murder has four limbs under section 300 of the Penal Code (“PC”). Only the first limb mandates capital punishment3 – under the other three, the courts have, the majority of the time, only given life imprisonment.

Let’s talk about the first limb. The first limb requires, essentially, that an accused person (1) commits an act that causes death (2) intending to cause death. If the prosecution can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that these two elements are satisfied, then the accused person can be convicted under s 300(a) PC, for which offence the punishment is the mandatory death sentence.

One must appreciate: Proving intention beyond a reasonable doubt is a high bar.

More often, accused persons are convicted under s 300(c) (if I remember correctly), which requires (once again, if I remember correctly) that an accused person commits an act that [ultimately] causes death (1) and (2) the harm caused by that act is sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death. I.e. if I hit stab you in the neck with a knife, meaning only to stab you in the neck (and not to cause death), but you actually die because of the stab wound, I might be convicted under s 300(c) PC, the maximum punishment for which is life imprisonment.

I’m oversimplifying, but you get the idea.

Misuse of Drugs Act (trafficking)

I feel personally miffed by the misrepresentation Singapore will execute by hanging individuals who possess drugs of any kind, of any amount. The mandatory death penalty is applicable mainly (only? must check) for drug trafficking.

True, drug trafficking has a rather expansive definition within the MDA. True also, that there is a legal presumption that carrying or being in possession of a certain minimum amount of a drug (each drug has a different weight requirement) means an accused has intent to distribute / traffic.

But true also is that this minimum amount is not by any measure small. It’s apposite to note that the minimum weight refers to the weight of the pure drug. Take, for example, weed (cannabis). The mandatory death penalty is imposed at 500 or more grammes. The average joint of weed has 0.32 grammes of pure cannabis.4 That works out to the mandatory death penalty only being imposed when someone trafficks (imports, sells, etc) over 1,500 joints/doses of weed – to me, it is a more than reasonable assumption to make that this person bringing in 1.5k joints’ worth of weed has an intent to distribute that weed… unless you gon’ tell me he’s planning to smoke all 1.5k joints? In a country with such strict surveillance and anti-drug laws?

Should the death penalty be legislatively disposed of?

My interpretation is that many arguments against capital punishment are contextualized within either murder or drug trafficking specifically. I feel different arguments are run against capital punishment in different contexts with accordingly different levels of effectiveness. Hence, I separate them into two sections: against capital punishment for murder and against capital punishment for drug offences.

Murder

One argument is premised on utilitarianism: The death penalty has no utility. The argument goes:

- The Singapore government (and some proponents of capital punishment for murder) claims that capital punishment is a deterrence.

- Statistics show that capital punishment is not a deterrence.

- Therefore, the Singapore government is wrong, and this should not be a reason for the death penalty.

- Barring any other valid reasons, the death penalty should not be imposed.

If you believe premises 1 and 2, premise 3 is true, and the conclusion of the argument must be true as well.

Another argument is based on moral repugnance: The state should never condone the killing of another human being, as human life is sacrosanct and valuable above all. The argument goes:

- Every human life is priceless. It is either (a) worth more than anything else, or minimally (b) worth more than whatever other moral benefit could be gained from executing a murderer.

- Either (a) the state must, minimally in this situation specifically, legislate on morals alone, (b) no conflicting moral ideals apply, or (c) there are conflicting moral ideals, but the right to live trumps all other rights / human life is the most important ideal and trumps all other ideals (in this situation).

- Thus, the state must outlaw punishments that take human life.

My personal issues with these arguments

First, it is logically impossible for statistics to conclusively show that, in Singapore, the capital punishment is ineffective. For a comparison to be made, there must always be a control group and a group with the changed variable. True, one may refer to studies done overseas. True also, that one may refer to speculative studies done locally. But these are as useful as they come: Studies done overseas are done with data collected overseas and studies done locally can only speculate or attempt to predict how crime rates would go up or down. I would argue that the only way to know for sure is to remove the death penalty and actually measure crime.

The three and a half years of Japanese occupation were the most

Lee Kuan Yew

important of my life. They gave me vivid insights into the behaviour

of human beings and human societies, their motivations and their

impulses. The Japanese Military Administration governed

by spreading fear. It put up no pretence of civilized behaviour.

Punishment was so severe that crime was very rare. In the midst

of deprivation after the second half of 1944, when the people were

half.starved, it was amazing how low the crime rate remained.

People could leave their front doors open at night … There were

no offences to report – the penalties were too heavy.

As a result I have never believed those who advocate a soft

approach to crime and punishment, claiming that punishment does

not reduce crime. That was not my experience in Singapore before

the war, during the Japanese occupation, or subsequently.

Second, at the beginning of this article (as it is quickly becoming) I posted a screenshot of an Instagram story. Therein, the poster reasons that Singapore should legislate according to what the majority deems morally correct. I take this test to its extreme and bring you back to pre-19th century America. People of color tend to cotton fields for fear of being punished for disobedience; they live as second-class human beings, if their employers even treated them as such. That slavery is perfectly alright is the predominant view of the land. Should slavery be kept legal, according to this argument? How about in Nazi Germany with the Holocaust? Is this proposed rule (that majority morality = decisive factor in legislative process) subject to any limitations, and if so why should it not be subject to one here?

Third, even if I accept that capital punishment has little deterrence value for murder cases, many of which are not planned assassination attempts but rather crimes of passion committed in the heat of the moment, what about drug trafficking cases, which are much less often – if not never – committed in such a “heat of the moment”? One might say the very fact that many Singaporeans have indeed heard of the capital punishment for drug trafficking and stay away from drugs as a result is ipso facto proof that the punishment does have a deterring effect.

Closing

It’s 4:23am and I need to sleep but I’m happy to entertain discussions on the topic, tele me @jedkhoo or something

I wrote my recent final paper for Intro to Legal Theory (y1 NUS law mod) on the death penalty in the context of

- Utilitarianism (focus on Bentham)

- Theories of natural law and internal morality (Finnis and Fuller)

- Critical legal studies/theory

- Interpretivism (Dworkin)

so I’m fairly interested in the topic. I think my final conclusion to that paper was that the death penalty should not be completely abolished as it can be applicable in certain circumstances where it is both most efficient (utilitarian) and morally justifiable (natural law; internal morality).

+ for crim we have to learn capital punishment anyway so :’-)

- https://www.amnestyusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Amnesty-Death-Sentences-and-Executions-2019.pdf and https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/courts-crime/11-judicial-executions-in-2022-none-in-previous-two-years

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capital_punishment_in_Singapore#:~:text=Capital%20punishment%20in%20Singapore%20is,death%20penalty%20under%20Singapore%20law. I have not personally verified this information, but I trust Wikipedia keeps it up to date. Regardless, the offences for which capital punishment is applicable is (I would argue) a secondary issue to whether capital punishment should be applicable at all.

- This was not always the case, but has been since 2012, if I’m not wrong. Prof Benny, don’t fail me if I got this wrong…

- https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/15/science/how-much-weed-is-in-a-joint-pot-experts-have-a-new-estimate.html#:~:text=To%20account%20for%20those%20variations,grams%20in%20the%20average%20joint.

Leave a Reply